Determinismus technologicus

Determinismus technologicus est theoria reductionistica quae ponit technologiam societatis progressum eius structurae socialis morumque culturalium determinare. Determinismus technologicus intellegere conatur modos quibus technologia cogitationes actionesque humanos afficit. Mutationes technologicae sunt primus fons mutationum socialium. Hoc vocabulum factum fuisse putatur a Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), sociologo et oeconomo Americano. Extremissimus autem determinista technologicus in Civitatibus Foederatis saeculo vicensimo ut videtur fuit Clarence Ayres, sectator Thorstein Veblen et Ioannis Dewey. Gulielmus Ogburn etiam extremo determinismo technologico innotuit.

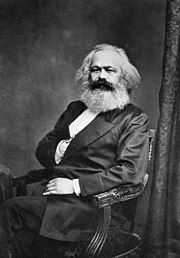

Prima interpretatio determinismi technologici de progressu socio-oeconomico magna a Carolo Marx posita est, qui philosophus et oeconomicus Germanicus arguit mutationes technologicas, praecipue facultates productionis, esse primum apud coniunctiones sociales et structuram organizationalem hominum valere, et coniunctiones sociales resque culturae ad ultimum in technologico atque oeconomico societatis fundamentis condi. Propositio Marxiana per societatem hodiernam penitus permanat, ubi plurimi credunt technologias rapide mutantīs vitam humanam magnopere afficere et mutare.[1] Multi auctores interpretationem historiae humanae a technologia determinatam cognitioni Marxianae tribuunt, sed non omnes Marxistae sunt deterministae technologici, ac nonnulli auctores num Marx ipse determinista esset dubitant. Praeterea, sunt variae determinismi technologici formae et rationes.[2]

De socialibus technologiae effectibus, Melvinus Kranzberg, historicus Americanus, inter suas sex technologiae leges definitive dixit: "Technologia nec bona, nec mala est; neque medium se gerit."[3]

Nexus interni

- Constructivismus socialis

- Thomas Lauren Friedman

- Informatica

- Raimundus Kurzweil

- Determinismus

- Fatalismus

- Hegemonia

- Liberum arbitrium

- Materialismus historicus

- Mutatio technologica

- Philosophia technologiae

- Timor technologiae

- Transhumanismus democraticus

- Somnambulismus technologicus

- Singularitas technologica

- Utopianismus technologicus

Motae

recensereBibliographia

recensere- Bimber, Bruce. 1990. "Karl Marx and the Three Faces of Technological Determinism." Social Studies of Science 20, no. 2 (Maius): 333–51. doi:10.1177/030631290020002006.

- Blauner, Robert. 1964. Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry. Sicagi.

- Cohen, G. A. 1978. Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence. Oxoniae et Princeton.

- Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. 1983. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave.' Novi Eboraci: Basic Books.

- Croteau, David, et William Hoynes. 2003. Media Society: Industries, Images and Audiences. Ed. 3a. Thousand Oaks Californiae: Pine Forge Press.

- Dusek, Val, 2006. Philosophy of technology: an introduction. Malden Massachusettae et Oxoniae: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1405111623, ISBN 1405111631, ISBN 9781405111621, ISBN 9781405111638.

- Ellul, Jacques. 1964. The Technological Society. Novi Eboraci: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Feenberg, Andrew. 2004. "Democratic Rationalization." In Readings in the Philosophy of Technology, ed. David M. Kaplan, 09–225. Oxoniae: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Furbank, P. N. 2007. "The Myth of Determinism." Raritan Fall: 79–87.

- Green, Lelia. Technoculture. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Hallett, Garth J. 2015. Humanity at the crossroads : technological progress, spiritual evolution, and the dawn of the nuclear age. Lanhamiae Terrae Mariae: Hamilton Books, An Imprint of Rowman & Little Field. ISBN 9780761865612, ISBN 0761865616.

- Huesemann, Michael H., et Joyce A. Huesemann. 2011. Technofix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment. Gariola Insula Columbiae Britannicae: New Society Publishers. ISBN 0865717044.

- Miller, Sarah. 1997. "Futures Work: Recognising the Social Determinants of Change." Social Alternatives 1 (1): 57–58.

- Murphie, Andrew, et John Potts. 2003. Culture and Technology. Londinii: Palgrave.

- Noble, David F. 1984. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation. Novi Eboraci: Oxford University Press.

- Noble, David F. 1986. Maschinenstürmer oder Die komplizierten Beziehungen der Menschen zu ihren Maschine. Berolini: Wechselwirkung-Verl.

- Ong, Walter J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Novi Eboraci: Methuen.

- Pérez Salazar, Gabriel. 2006. El determinismo tecnológico: una política de Estado. Revista Digital Universitaria. PDF.

- Postman, Neil. 1992. Technopoly: the Surrender of Culture to Technology. Novi Eboraci: Vintage.

- Sawyer, P. H., et R. H. Hilton. 1963. "Technical Determinism." Past & Present Aprilis: 90–100.

- Schelsky, Helmut. 1961. Der Mensch in der wissenschaftlichen Zivilisation. Coloniae.

- Servaes, Jan, ed. 2014. Technological determinism and social change: communication in a tech-mad world. Lanhamiae Terrae Mariae: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739191248.

- Smith, Merritt Roe, ed Leo Marx, eds. 1994. Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism. Cantabrigiae Massachusettae: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262691673, ISBN 0262193477, ISBN 0262691671.

- Staudenmaier, John M. 1985. "The Debate over Technological Determinism." In Technology's Storytellers: Reweaving the Human Fabric, 134–148. Cantabrigiae Massachusettae: Society for the History of Technology et MIT Press.

- Winner, Langdon. 1977. Autonomous Technology: Technics-Out-of-Control as a Theme in Political Thought. Cantabrigiae Massachusettae: MIT Press.

- Winner, Langdon. 1986. "Do Artefacts Have Politics?" In The Whale and the Reactor. Sicagi: University of Chicago Press.

- Winner, Langdon. 2004. "Technology as Forms of Life." In Readings in the Philosophy of Technology, ed. David M. Kaplan, 103–13. Oxoniae: Rowman & Littlefield.

- White, Lynn. 1966. Medieval Technology and Social Change. Novi Eboraci: Oxford University Press.

- Woolgar, Steve, et Geoff Cooper. 1999. "Do artefacts have ambivalence? Moses' bridges, Winner's bridges and other urban legends in S&TS." Social Studies of Science 29 (3): 433–449.

Nexus externi

recensere- Chandler, Daniel. "Technological or Media Determinism."

- Kimble, Chris. "Technological Determinism and Social Choice."

- McCormick, Megan. "Technology as Neutral."

- Rule, Colin. "Is Technology Neutral?"